Taking the Time to Notice

Our students are busy – busy playing, learning, talking, thinking, discovering, experimenting, wondering. In each of these actions, our students reveal to us their thinking if we are ready to notice. When we notice, we can make our students’ naturally occurring goals explicit and we can coach them toward their goals.

In purposeful play, mathematics, and literacy, noticing is a powerful teacher action that can reveal students’ naturally occurring goal setting processes, build meaningful student-teacher and student-student relationships, and inform instructional decisions.

- In purposeful play, noticing is observing student interests – their preferences for location and peers, their choice of materials, their conversations, their play themes and topics (Mraz, Porcelli, & Tyler, 2016).

- In mathematics, professional noticing of students’ thinking includes three skills: attending to strategies, interpreting understandings, and deciding how to respond based on understandings (Jacobs, Lamb, & Philipp, 2010).

- In reading, noticing is appreciating choice and monitoring independent decisions, including choice for texts, topics, strategies, responses, projects, and partners (Moses & Ogden, 2017).

- In writing, noticing is the first step to developing students’ awareness and ability to name both what they already know and can do as writers and the patterns they discover in writing (Johnston, 2004).

In order to explicitly coach our students’ in-the-moment goals, we must first notice them. Follow these five steps during purposeful play, mathematics, reading, writing, and beyond to intentionally notice.

1. Choose a day and time when noticing will be your primary task. After your mini-lesson, after students are settled into their independent or partner work, this is prime time to notice. Spend 15-30 minutes noticing. By choosing a day and time in advance, you will protect your noticing time and make it a priority.

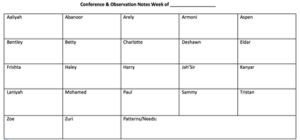

2. Have a clipboard, pen, and chart to record your noticings. An open observation chart is a table with each student’s name in a box and space to record your noticings. Recording will make your noticings visible, and therefore actionable. You will be able to reflect back on your noticings to find patterns, surprises, and questions. You can then use your noticings to plan instruction and coach students’ goal work. Here is a sample open observation chart:

3. Spend more time listening and watching than talking. This noticing time is not a teaching moment. It will lead to teaching moments, but right now, you are there to listen and watch. Noticing with these questions in mind may help you to be intentional and targeted while remaining open to students’ in-the-moment decisions, language, and actions:

- What are students gravitating toward? What is a popular material/choice and why?

- Who typically works/plays here? Do all students eventually work/play here?

- Is there a balance of independent and collaborative work/play?

- Are there enough choices or “meaty” enough tasks to sustain work/play for at least 30 minutes in one area or on one task?

- Are content areas integrated when possible? Are there materials that can be combined?

- Are students engaged in doing the “real work” of readers, writers, mathematicians, or some other role?

4. If you talk, ask open questions. When you are noticing, you can be quiet and just listen. If you need to speak, ask students open questions: What are you working on? What are you using? Why? How did you decide to create this? Why do you think that’s happening? Ask questions that communicate your genuine wonder and your desire to understand your students’ thinking. Taking the time to actively listen tells your students that you value them.

5. Stay. Rather than moving from student to student and space to space, stay in one area with one student or one group of students for 15-30 minutes. The depth and breadth of student thinking is often revealed over time as they engage more deeply in a task.

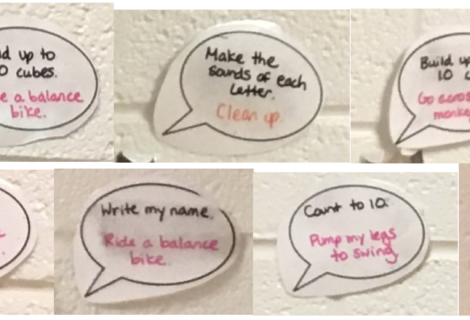

Noticing requires us to slow down, to pause with our agendas and to-do lists, and to listen and watch. Noticing is paying attention to students’ in-the-moment decisions, language, and actions. When we take the time to notice, we will discover our students’ naturally occurring goals.

For more on student goal setting and how workshop model can support student goal setting, register for the VaSCL workshop Differentiation in the Workshop Model: Matching Tasks to Students (Grades PreK-5) on March 19th at https://www.vascl.org/.

References

Jacobs, V.R., Lamb, L.L.C., & Philipp, R.A. (2010). Professional noticing of children’s mathematical thinking. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 41(2), 169-202.

Johnston, P. (2004). Choice words: How our language affects children’s learning. Portsmouth, NH: Stenhouse.

Moses, L. & Ogden, M. (2017). What are the rest of my kids doing? Fostering independence in the K-2 Reading Workshop. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Mraz, K., Porcelli, A., & Tyler, C. (2016). Purposeful play: A teacher’s guide to igniting deep and joyful learning across the day. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.